After more than a century of ignominy, the father of English literature, Geoffrey Chaucer, appears to have emerged unscathed and renewed from his academic-inspired #MeToo shame. The Canterbury Tales author has been regarded as a misogynist and rapist since 1873 when a newly discovered 14th century court document appeared to name Chaucer as a sexual predator. However, further research released this week suggests that he has been needlessly maligned in the hallowed halls of academia.

A Huge Misunderstanding?

At the heart of Chaucer’s alleged crimes is a court document dated around 1380, in which Cecily Chaumpaigne released Chaucer from “all manner of actions related to my raptus.” The word “raptus” originates from the Latin version of “seizure.” This has been interpreted in modern times to mean “rape” or “the forcible abduction of a woman.” And so began the decimation of the character of one of literature’s most important and influential figures. But sometimes, academics are all too keen to run with an interpretation that bolsters the prevalent ideology.

At the heart of Chaucer’s alleged crimes is a court document dated around 1380, in which Cecily Chaumpaigne released Chaucer from “all manner of actions related to my raptus.” The word “raptus” originates from the Latin version of “seizure.” This has been interpreted in modern times to mean “rape” or “the forcible abduction of a woman.” And so began the decimation of the character of one of literature’s most important and influential figures. But sometimes, academics are all too keen to run with an interpretation that bolsters the prevalent ideology.

A stunning revelation this week by two scholars has now upset the narrative by revealing that the word “raptus” is likely in no way connected to sexual assault.

Sebastian Sobecki, an English professor at the University of Toronto, and Euan Roger of the British National Archives made a stunning claim. Rather than Chaucer and Chaumpaigne being on “different sides” of the legal case, “they are both defendants. And that changes everything.”

And Clarity Shines Through…

The researchers point to other contemporaneous documents that show the pair were in court as co-defendants in a labor dispute after Chaumpaigne left her position in one household to go and work for Chaucer. How they discovered these documents is worthy of a Dan Brown novel.

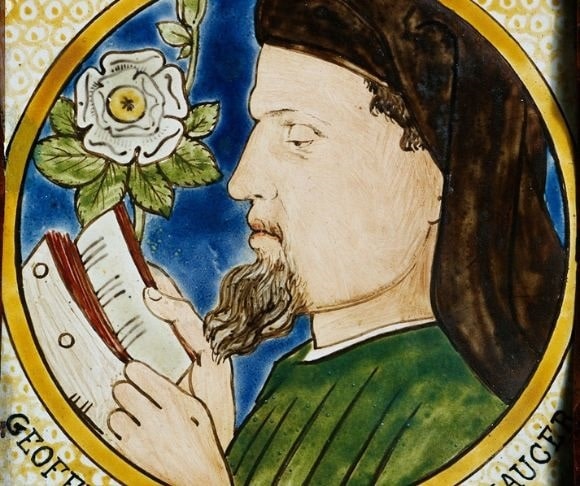

Geoffrey Chaucer (Photo by © Historical Picture Archive/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images)

The scholars were hunting for an original document that allegedly supported the claims made against Chaucer. They found it but noticed something was amiss. In fact, the paper – a warrant – showed that Chaumpaigne had hired two lawyers not to prosecute the author but rather to defend herself against charges of leaving the service of a man named Thomas Staundon without authorization.

With this fascinating conundrum in hand, the researchers sought to find other court papers from the same period. In Chaucer’s time, the highest court in the land was the King’s Bench (and remained so for a further 500 years); the records are kept in a salt mine in the county of Cheshire, in the northwest of England. This archive is roughly 100 miles in length and growing every year; the lack of humidity and rodents means the records are perfectly preserved.

When the requested documents were delivered, they appeared to be in their original wrappings, and the pages held together with lines of catgut filament. What was revealed is that Chaucer and Chaumpaigne were defending themselves against charges filed under the Statute of Labourers.

The scholars note:

“The Statute and related Ordinance were enacted in response to the economic difficulties that emerged after the first outbreaks of the plague in England in 1348, and were designed to provide new labour regulations in a restricted labour market, to combat rising wages, and to prevent the poaching of servants from employment on the promise of more generous terms.”

Staundon’s (the accuser) original charge reads ” ‘the aforesaid Geoffrey admitted and retained Cecily Champayn, formerly the servant of the aforesaid Thomas, in his service at London, who has departed from the same service before the end of the agreed term, without reasonable cause or licence of Thomas himself, into the service of the said Geoffrey.”

And so, the researchers explain, when Chaumpaigne describes the “manner of actions related to [her] raptus,” she is, in fact, talking about her decision to move to new employment and not about any sexual misconduct on Chaucer’s part.

But, But, Believe All Women?

One would assume that with this fresh vindication after 150 years of being – as one New Hampshire English professor described him – “a rapist, a racist, an anti-Semite,” that jubilation would ensue in the halls of literary academia. Sadly, this does not appear to be so.

As part of an outreach consultation by the researchers, several “prominent feminist scholars” were invited to provide additions in the soon-to-be-published journal detailing the findings. Surely with documentary proof that Geoffrey Chaucer was not the villainous creature, so many in the field of Chaucer Studies have contended, the tune would change?

(Photo by JHU Sheridan Libraries/Gado/Getty Images)

Professor Samantha Katz Seal said of the newly-discovered evidence that it did not change the fact that Chaucer’s poetry was “embedded in a systematic rape culture.” Further, she noted that the “raptus” narrative has been “a pedagogically useful tool” for introducing questions of sex and power.

“My classroom is still going to be talking about rape, violation and consent, because that’s what’s in the poetry,” she said. “But we’ll also be thinking about the author as a construct, as something we buy into and make together.”

Another scholar the duo approached was Sarah Baechle, who, after reviewing the evidence, wrote an article stating that approaches to the poet are” No longer burdened with assessing Chaucer’s guilt or Chaumpaigne’s victimization, we may adopt, instead, a structural approach, examining how Chaucer’s rape narratives reproduce harmful myths about women, sex, and consent that perpetuate assault.”

Chaucer – Tainted But Resilient

So perhaps, despite evidence to the contrary, Chaucer’s legacy will forever be tainted by other people’s mistakes and misinterpretations. And it seems that even modern society, with all of its talk of truth and tolerance and forgiveness, is not willing to let go of a useful narrative that has spurred on so many careers that rely on anger and misandry.

And yet, for those who do value truth, and literature, and history, a small celebration might be allowed, as we realize that buried in vaults, and archives, and even salt mines across the world, are more secrets and more discoveries, still to be brought forth. History is not dead, and the future is bright with its continued promise.