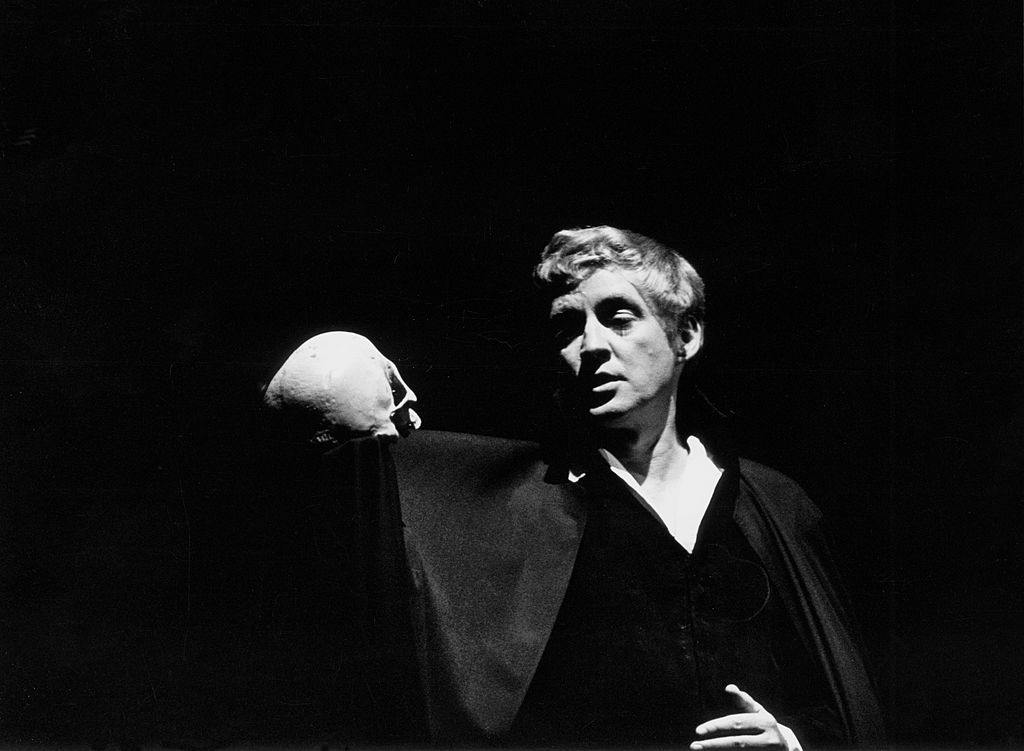

To vote, or not to vote: that is the question:

Whether ‘tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous polling,

Or to take up mail-in ballots against a sea of negative surveys,

And by opposing end them? To ignore: to vote;

No more; and by a vote to say we end

The heartache and the thousand fake news stories

That media is heir to, ‘tis a consumption

Devoutly to be wish’d. To ignore, to vote;

To vote: perchance to win: ay, there’s the rub.

With the midterm primary season done and just eight weeks to go until the shape of the next Congress is finally known, polling and the interpretation of the numbers is about to become America’s new national pastime. But why do political watchers still have such faith in this once vaunted industry? With inherent bias and an effort by survey makers to persuade rather than inform, potential voters are confronted with the indecision so exemplified by Prince Hamlet’s fourth soliloquy. To trust the pollsters or not: that is, truly, the question.

With the midterm primary season done and just eight weeks to go until the shape of the next Congress is finally known, polling and the interpretation of the numbers is about to become America’s new national pastime. But why do political watchers still have such faith in this once vaunted industry? With inherent bias and an effort by survey makers to persuade rather than inform, potential voters are confronted with the indecision so exemplified by Prince Hamlet’s fourth soliloquy. To trust the pollsters or not: that is, truly, the question.

Not All Polling Is Created Equal

American voters are all too familiar with the tsunami of 2016 polling suggesting that Hillary Clinton was destined, with 95% certainty, to take the White House. The election result was a denouncement of survey methodology and a wake-up call to those who believed poll companies were above partisanship. Subsequent prognostications have proven equally flawed. As George Orwell might have put it: all polls are equal, but some polls are more equal than others.

When the media are engaged in a bias battle for their chosen candidate, questions of poll reliability and quality are thrown out the window with journalistic integrity. If a poll favors the Fourth Estate’s choice, it is presented as defining evidence that the contest is all over but the singing. For example, a recent Franklin & Marshall poll gave Pennsylvania Democrat Senate hopeful John Fetterman a 13-point lead over Republican Mehmet Oz. The topline result was published by numerous media organizations including MSN, Bloomberg, and Yahoo. But how straightforward was the actual survey?

The first point to take note of is that the sample size was small – just 522 respondents compared to an industry standard of at least 1,000. Next was that it covered “registered voters” rather than “likely voters.” In the polling game, those who are likely to cast a ballot are a far more reliable indicator than those who just happen to be registered in their state. And then there are the “push questions.” Right before asking about candidate favorability, the survey posed six questions directly related to the events of January 6, 2021, at the US Capitol. Such lines of enquiry are designed to elicit a specific response: No one wants to be seen as a criminal sympathizer, even to a stranger.

And then comes the element of gaming the aggregate …

A Game of Sums

(Photo by Octavio Jones/Getty Images)

An outlier poll – one that gives Fetterman a 13% lead, for example – is still taken into account when an aggregate number is formed. An aggregate represents an average of all polls. So, although most surveys give the Democrat contender a lead over his GOP rival, the inclusion of such a wide-margined poll pushes the figure even higher when an average is taken. Another poll, by Echelon Insights, suggests Fetterman has a 21-point advantage over Oz; this is a number that should cause eyebrow raising among even the Democrat’s most ardent supporters. And yet this too will be used to form the final aggregate.

When potential voters see a huge margin between candidates, it may discourage the casting of a ballot – after all, why bother to waste your time when your preferred representative has little to no chance of winning? And this is, perhaps, why outlier polls are so advantageous to political parties. If your opposition’s base fails to turn out at the ballot box, it can make all the difference in a close race; the polling becomes a reality because it has affected the outcome rather than anticipated it.

Hamlet’s Dilemma

In Shakespeare’s play, Hamlet was bedevilled by indecision; his failure to act was his curse. In his tortured mind were doubts about what he suspected to be true, and yet his vacillation denied him resolution. The candidates for the November elections are in place, and all that remains is for voters to make a decision. Outrageous polling can feed into this electoral dilemma, and that may be its very purpose.

If the American voter has the knowledge that pollsters are often the tools of politicians and strategists, what dreams, indeed, may come. And finally, all their surveying sins could – and should – be remembered.